Every unhappy terrorist movement is unhappy in its own way, and the global jihadist movement is no exception. Disagreements over targeting, tactics, organization, and the fundamental question of what it means to be a good Muslim have plagued the movement since its inception and remain a source of weakness.

As the Islamic State declines, these differences become even more important. The Islamic State has lost the bulk of its territory in Iraq and Syria, but it is likely to endure as some form of insurgency and, beyond that, as a terrorist movement. Still, playing the leadership role the movement claimed when it declared the caliphate in 2014 will be harder. Al Qaeda, for its part, has triedto play a longer game, but it too remains weak and may not be able to reclaim the leadership standard.

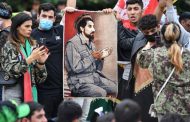

Yet even as there is no clear leader, the broader movement remains robust. Jihadist groups, some of which have ties to al Qaeda and the Islamic State, are active in Yemen, the Maghreb, India, the Philippines, and of course Syria, among many other locations. In Europe, the jihadist movement enjoys support from too many Muslims, enabling it to attract fighters and inspire terrorist attacks.

This broad movement, however, is divided over several key questions. A very basic one concerns who is a “true” Muslim. Every religion, even the most accepting, has a line that separates believers from nonbelievers. Islam is no exception: It would be hard to claim to be a Muslim if one did not believe in God and did not consider Mohammed his prophet. Jihadists are often much stricter. Although jihad is generally justified as defending Muslims or reclaiming Muslim land from unbelievers, in practice many jihadists condemn whole groups of nominally fellow Muslims to the status of unbeliever (kafir).

This goes against the approach most Muslim scholars have historically taken with this issue, as they’ve heeded the Prophet Mohammed’s warning that being quick to accuse others of unbelief can lead to debilitating divisions among the faithful. Some jihadists contend that only observant Muslims truly are Muslims and that all others are apostates.

Many would also say that only Sunni Muslims count: Shiite Muslims are the majority in Iraq, Bahrain, and Iran, but under jihadists’ strict interpretation of monotheism, Shiites are not true Muslims because their veneration of Ali, the fourth caliph and the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, gives him semi-divine status. Alawites, who control the Syrian government; Houthis, Yemenis who follow a different form of Shiism; and other religious minorities such as the Ahmadis, Druze, and Yazidis are also beyond the pale.

Others would go further and draw the line between Salafis — a puritanical form of Sunnism that rejects traditional politics, manmade laws, and anything that smacks of human innovation — and all others, rejecting non-Salafi Islamist groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood as insufficiently pure. Still, others would draw the line between those Salafis who embrace jihad and those who don’t — you’re either with us or against us.

Having drawn the line between true believers and others, the next question is what to do about those who fall short. The Islamic State and, before that, al Qaeda in Iraq made their names targeting Shiites and Sunni Muslims who cooperated with enemy governments, arguing that both deserved death for their impious allegiances.

In Algeria in the 1990s, some jihadist groups went so far as to slaughter ordinary Muslims who tried to stay out of the fray, arguing that their noncooperation was tantamount to rejecting the faith. Al Qaeda, by contrast, has usually called on its followers to ignore these groups and, ideally, proselytize to put them on the true path.

The movement is also divided over who is a legitimate target. More broadly, there are divisions over the concept of tatarrus, or the killing of innocents as part of military operations (what the Pentagon would call collateral damage). Muslim scholars, like their Christian counterparts, have wrestled with how to balance the reality of war and its needs with their faith’s call to protect the innocent. Many jihadist groups have lost popular support when they killed innocents, especially innocent Muslims, in their operations. Two al Qaeda attacks against residential compounds in Riyadh in 2003 killed almost 20 Saudis — far more than the number of Americans — and drew widespread condemnation among ordinary Saudis. The May 2003 bombings killed nearly as many Muslims as infidel Westerners. The attack that followed in November — during the holy month of Ramadan, as it happened — killed and injured almost exclusively Muslims. Some 36 children were wounded. Ordinary Saudis turned sharply against the group.

Al Qaeda in Iraq’s decision to target hotels frequented by Westerners in Jordan, one of which was hosting a local couple’s wedding, had a similar effect there. Al Qaeda has tried to learn its lesson from this. Especially with regard to Muslims, the group is far more discriminating in its targeting than it was 15 years ago. When the Islamic State captured and murdered Western aid workers in Syria, for example, al Qaeda’s Nusra Front decried this as “wrong under Islamic law” and “counterproductive.”

Abu Omar Aqidi, a senior Nusra Front militant, even tweeted to publicly call on the Islamic State to release Peter Kassig, an American aid worker (and convert to Islam) who had “performed a successful [medical] operation under bombardment by the regime” on Aqidi himself and treated other jihadists. After the infamous immolation of a Jordanian (Muslim) fighter pilot, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula denounced the video as “conclusive proof of ISIS deviance.”

These differences are obscure to many, but the movement also has a basic question regarding organization: Should it be strictly hierarchical or far more decentralized? Al Qaeda in the 1990s and later the Islamic State along with its predecessor organizations usually pushed hierarchy: They have a top leader, senior lieutenants, committees to handle key issues such as security and media, and so on. The Islamic State also tried to replicate this at a local level to ensure order and control.

The relentless counterterrorism campaigns of the United States and its allies, however, made hierarchies dangerous. The killing or capturing of key leaders could bring a group to a temporary halt or at least severely limit operations. In addition, the constant communication needed to run a large insurgency or global terrorist movement risked revealing the whereabouts of key figures.

The Islamic State still favors some degree of hierarchy, but other groups have called for far more decentralized operations. These are harder to disrupt, but they run the risk of fragmentation. Even if the organization does set out clear instructions regarding tatarrus and other targeting concerns, it is hard to enforce order, running the risk that unauthorized actions of a local cell or foreign affiliate could discredit the broader group.

The jihadist movement is also profoundly divided on the question of the caliphate. The Islamic State has made its reputation in part on declaring its return. Al Qaeda, however, has waffled in many public statements because of the concept’s popularity and the group’s longterm goal of establishing an Islamic state of its own. In private, though, it has often been scathing, arguing that the jihadist movement as a whole does not enjoy the popular support necessary for a caliphate to survive and that establishing state structures in a given area simply tells the United States and its allies where to bomb.

Even below the level of the caliphate, the groups disagree on whether to impose Islamic law in areas they control. The Islamic State contends that it is its religious duty to do so, and of course, a caliphate would not be a true caliphate if it did not govern according to Islamic law. In areas where al Qaeda-linked groups have controlled territory, however, they have vacillated between strictly imposing Islamic law and taking a more lenient approach of educating the locals or even leaving it to local leaders to settle disputes and otherwise rule.

In general, al Qaeda and associated groups favor a more “hearts and minds” approach of providing services, working with local leaders and partnering with other rebel groups. The Islamic State, however, wants to crush necks and spines, displacing local leaders, and ensuring its own power. It often puts foreigners in control of areas it conquers, while al Qaeda groups prefer local leaders. In Syria and other places with many jihadist groups, the Islamic State demands their loyalty while al Qaeda has called for partnering with, and often taking a back seat to, other Syrian rebel groups.

The movement also differs as to how much to focus locally and regionally vs. those who want to focus on the United States or other Western countries. Most groups try a mix of both: Al Qaeda at the time of 9/11, for example, spent the bulk of its money and forces helping the Taliban and used its camps in Afghanistan to train fighters focused on fomenting insurgencies in the Muslim world; at the same time, it engineered a massive terrorist attack on the United States.

Similarly, the Islamic State mostly pursued the consolidation and expansion of its caliphate, but it has also tried to encourage attacks on the West and used operatives to carry out bloody strikes such as the 2015 Paris attacks. Having it both ways, however, makes it harder for the groups to concentrate their resources and risks attracting new enemies, which more local rebel groups understandably hate.

Al Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, for example, has declared that it will not attack the West and ostensibly separated from the al Qaeda mothership to demonstrate to local allies that it would not stand in the way of their receiving military aid from the United States and its partners.

An important question is whether these are differences in objectives or simply differences in priorities. If jihadists disagree on fundamental outcomes, then any unity of purpose or organization will be much harder to achieve. If the question is simply one of priorities, then changes in circumstances can bring different factions together in the name of expediency.

Questions of tatarrus or the precise line where apostasy begins and ends mean little to most foot soldiers. Data from captured Islamic State records showed that 70 percent of recruits claimed they had only a basic knowledge of Islam. But some of these questions have a tremendous impact on the appeal of different groups. The revival of the caliphate, for example, proved compelling to many recruits and, regardless of its perceived legitimacy among purists, the temptation to play this popular card will be there in the future.

It’s always tempting to urge the United States to try to play up these divisions, and I’ve done so myself at times. The U.S. track record of influencing the jihadist dialogue, however, ranges from poor to nonexistent, and deliberately trying to generate ever more extreme factions isn’t wise. But these internal fissures do hamper U.S. enemies and do some of the work for us. At the very least, they expend precious time and energy trying to one-up rival groups in their propaganda. At most, the differences lead to actual shots fired or recruits and donors being turned off by infighting.

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...