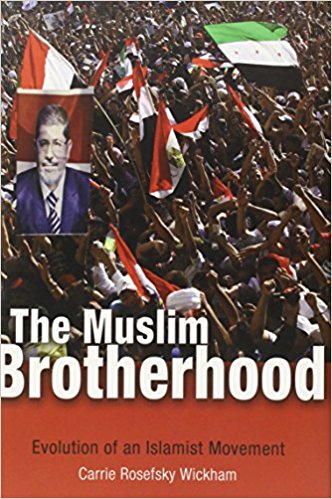

Wickham, known for her 2002 study Mobilizing Islam: Religion, Activism and Political Change in Egypt, continues to examine religion and political change in Egypt. This time she focuses on the era before the electoral win of the presidency by Muslim Brotherhood leader Muhammad Mursi, whose reign lasted just one year until mid-2013.

A political scientist at Emory University, Wickham published this study just as the Brotherhood’s presidential star was falling. In nine chapters, she illuminates the early years of the Brotherhood’s founding after 1928, its growth, how it coped with its branding as an illegal movement throughout much of its history, and finally the trial and error of its foray into electoral politics.

Muslim Brotherhood founder Hasan al-Banna (1906-49), and Muhammad Mursi (1951), the first president in Egypt on behalf of the Muslim Brotherhood (30 June 2012 to 3 July 2013), removed by a “coupvolt”

Wickham also spends some time on similar Islamist groups in Jordan, Kuwait, and Morocco. Drawing on one hundred interviews, Wickham concludes that none of the Islamist groups moved toward moderation, including the Muslim Brotherhood. She maintains that such groups resist easy categorization and indicates where “hybrid agendas” illustrate the collision between the concepts of democracy and those of the Islamic Shari’a law.

The author proceeds cautiously, almost surprised by her insights: “Over the course of more than twenty years of research on the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, the more I have learned, the more struck I’ve become how little we know about its internal operations. For example, we have yet to fully understand the Brotherhood’s methods for recruiting and socializing its members; the size and regional, generational, occupational, and class composition of its base; the sources of its financing; the activities of its local cells and branch offices; and the mechanisms available to its leaders to promote conformity and limit the expression of dissent.” Now I briefly add a few Berlin related insights, before returning to Wickham’s well-done book.

As Germany nurtured anti-Christian brotherhoods to jihadize pan-Islamism (since 1900 also called “Islamism” for short) in colonies of her rivals beginning two decades before 1914, Berlin promoted since 1928 the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood as number nine of Islamist groups or related supranational entities. The eight Muslim brotherhoods (Arabic tariqāt) in Max von Oppenheim’s jihad plan for kaiser Wilhelm II as potential policy plat-forms and counterweight also against increasing left groups were in November of 1914:

- As-Sanusiyya, 2) an-Naqshbandiyya, 3) as-Shishtiyya, 4) as-Suhrawardiyya, 5) al-Qa-diriyya, 6) al-Mahdiyya, 7) al-Ikhwaniyya, and 8) chosen scholars from the al-Azhar Uni-versity and Dar al-Ulum in Cairo (and the Indian Dar al-Ulum, Diyuband), usually Sufis.

In my count arose then the 10) Khilafat and 11) Khaksar movements, 12) Jamaat-e Isla-mi, founded in 1941. After World War Two, the ruling nationalists as Abd an-Nasir sup-pressed some of those groups or movements in the Middle East. Members of the Muslim Brotherhood fled to Western Europe and neutrals like Switzerland. After Anwar as-Sadat came to power in Cairo and released Islamists from prisons, a wave of Islamism ensued since the 1970s. Then a time started of organizational experiments with “political Islam” at the dawn of a global era. As number 13) al-Qaida emerged about 1988 in Afghanistan.

Of course, there were other branches, some not long living or too local to be counted in the big picture. Within the German capital, Islamists unfolded a network before the Nazis came to power, via the 1927 Islam Institute, and the 1931 chapter of the Islamic World Congress. In Berlin led by the Syrian Islamists Abd an-Nafi’ Shalabi and Husain Danish, the Euro-Islamist Shakib Arslan of Geneva and the grand mufti Amin al-Husaini of Jeru-salem guided them. Since 1958 Said Ramadan acquired this guidance role in Geneva for Western Europe. As before, the Islamists turned against the growing Soviet influence too.

All of them, and the Egyptian Abd al-Aziz Jawish of von Oppenheim’s jihad circles in World War One, swayed the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood Hasan al-Banna. They expanded their ties in the Nazi era as Berlin and al-Husaini supported him. This was also true with the other brotherhoods such as the al-Mahdiyya in Sudan or the as-Sanusiyya in Libya. Thus, the Muslim Brotherhood grew as one of a dozen organizations of Islamism, the 1800+ ideology of pan-Islamist unity, mostly opposed to modernity and open society.

Getting back to this book, a next edition would be strengthened with more key Arabic and European sources. Transcriptions should avoid dialects (thawabit rather than thauwa-bet) and be exact (Islam huwa al-Hall not al-Hal). Despite these minor concerns, Wick-ham’s book provides a solid guide to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Wolfgang G. Schwanitz

Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, The Muslim Brotherhood, Evolution of an Islamist Move-ment, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2013. 384 pp.

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...