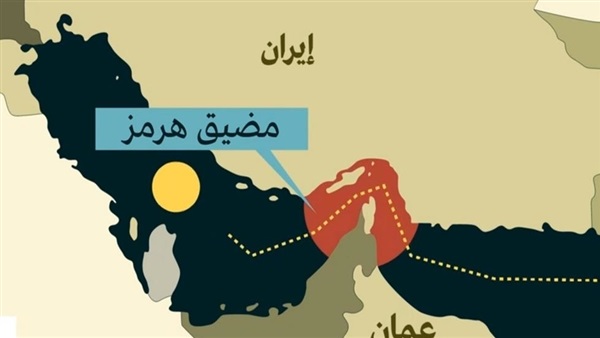

How did Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s first foray as a conflict mediator go when he traveled to Tehran last week? In a joint news conference with Abe, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani explicitly blamed tensions on the United States’ economic war against Iran. Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei expressed that Iran will never negotiate with the U.S. Two tankers — one operated by a Japanese company — were attacked just beyond the Strait of Hormuz in the Gulf of Oman while Abe was still in the country. Within 24 hours, the U.S. attributed the attacks to Iran, drawing immediate rebuke from Iranian officials who argue the U.S. is running an “Iranophobic campaign.”

So does this means Abe’s endeavor to mediate tensions was a failure? Not necessarily.

Those arguing that Abe failed in Iran misunderstand what mediation is. First and foremost, it is not a one-off consultation. When two parties are in a seemingly deadlocked state of reciprocal escalation as the U.S. and Iran are, mediation must happen in phases. In this early phase, Abe’s goal is simply to facilitate communication; in other words, to create a channel for negotiation that neither side is willing or able to create on its own. With his trip to Iran, Abe successfully initiated his shuttle diplomacy.

Abe arrived in Tehran with the White House’s blessing to open up talks with Iran. Prior to his trip, Abe made separate calls to leaders from the U.S., United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Israel to ensure he accounted for the myriad interests at play. His engagement in Iran presented the U.S. desire to achieve diplomatic resolution to potential military conflict, and reports indicate that Abe even had specific messages from the U.S. government to deliver to Iran’s top officials.

In addition to meeting with Rouhani, Abe met directly with Khamenei, with whom an audience is not commonly extended. In doing so, Abe and his team were able to communicate with the highest echelons of Iran’s government. Further, after returning to Japan, Foreign Minister Taro Kono and Abe both conducted phone calls with their American counterparts, closing the loop with the State Department and White House.

Abe’s visit also prompted the Iranians to signal important messages related to negotiations. At first glance, the response from Iranian officials seemed counterproductive, but for a government that said it does not want to engage with the U.S., it communicated quite a bit in English and much via Twitter — Trump’s favorite social media platform.

From the perspective of a former intergovernmental negotiator, there were several signals of note. When Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif asserted that the “cause of tension is clear: U.S. violation of JCPOA [and] imposition of economic war,” he was expressing that Iran’s primary interest is removal of sanctions but a major concern for reentering formal negotiations is a dearth of trust.

When Khamenei questioned U.S. sincerity based on its imposition of additional sanctions shortly after Trump’s blessing for Abe to mediate tensions, he was signaling that coercive tactics will not work with Iran. Khamenei later added that Iran “won’t repeat the same experience” it had in negotiating the JCPOA only to have the U.S. later leave the agreement. This means a new method of engagement different in process and content from JCPOA negotiations is necessary for resolution of bilateral tensions.

Finally, Khamenei reiterated Iran’s policy line that the government opposes nuclear weapons, but he added, “know that if we ever intended to produce nuclear weapons, the U.S. wouldn’t be able to do anything against that.” There, he signals that ceasing nuclear development is still negotiable, but only through incentives, not coercion.

Other signals that many officials and observers will highlight are the tanker attacks that took place on June 13, but from a mediation standpoint, it is more important to focus on what they were not, rather than what they were.

The attacks were not a new form of escalation — they were a repeat of what happened in mid-May. In both sets of incidents, attackers disabled foreign tankers, which affected oil prices and sent a message that destablization of the region has consequences for world powers both inside and outside of Southwest Asia.

Also, the attacks were not done by uniformed military and are not easily attributable. They were not meant to result in loss of life and were not done in ports on foreign soil. This means that they will fail to meet the threshold for an “armed attack” as defined under international law and will draw mixed reactions from the international community.

There are three takeaways from this. First, Abe is doing what he is supposed to be doing. He got Iran to do some signaling and may have received some discreet messages to deliver to the White House. It would not be unusual for parties in mediation to have vastly different public and private messaging. No mediator solves a conflict in the first engagement, and Abe is doing what he must in this first phase.

Second, coercive negotiation tactics from the U.S. will not work. Assuming the tanker attacks are linked to Iran, they demonstrate that Iran is seeking its own method of coercion through security incidents short of a United Nations-recognized “armed attack.” What this means is that Iran can direct actions that have a major security impact — in particular, on economic and energy security — without provoking a legally founded international military response. In that way, it suggests that U.S. coercive tactics will only beget greater escalation, even if that does not immediately mean the outbreak of war.

Third, given the risks associated with coercive tactics, an incentive-based approach will be necessary. Since neither side is willing to offer concessions, this is where mediation is critical. If Abe gets past phase one in facilitating communication, his role in phase two will include mediating incentives.

From here, it will be important to see if the U.S. offers Japanese officials additional information or proposals to return to Iran, whether through senior or working levels. The Japanese government will need to continue engaging both sides. The U.S. and Iran may be willing to broker a de-escalation of tensions without ever engaging face-to-face. However, a longer-term resolution will eventually need the two sides to meet, so the Japanese government must try to entice the two parties to mediated engagement on neutral ground. That will likely take time, trust-building measures, and a lot more shuttle diplomacy.

It is possible that Abe did not realize he signed himself up for such a long haul endeavor, and his mediator role will be met with a busy political calendar that includes hosting the Group of 20 summit later this month and the Upper House election in July. Still, as many government officials and outside observers have noted, continued escalation between the U.S. and Iran has dire consequences, and it is unlikely that the Abe administration will suddenly give up on what it set out to achieve through mediation. There are still miles to go in Abe’s endeavor, and no one should be judging the Japanese government this early in the process.

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...