In the first weeks of 2011, Osama bin Laden was worried. For five years, he had concealed himself and his extended family—wives, children and grandchildren—in a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, but now it appeared that his carefully constructed hideaway was coming apart. His longtime bodyguards were two brothers, members of al Qaeda whose family originated nearby. They did everything for bin Laden, from shopping in the local markets to hand delivering his lengthy memos to other leaders of al Qaeda.

But bin Laden’s bodyguards had become fed up with the risks that came with protecting and serving the world’s most wanted man. Bin Laden confided to one of his wives that the brothers were “getting exhausted” and planned to quit. Things got so bad that on January 15, he wrote a formal letter to them, despite the fact that they all lived together, acknowledging how angry they were with him and begging them to give him time to find new protectors and a new hideout (the compound was registered in the name of one of the brothers). He set down in writing that they had agreed to separate by mid-July.

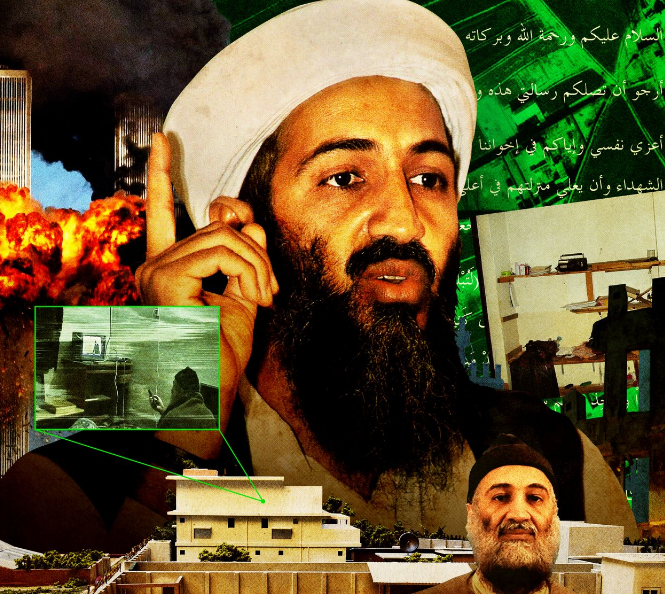

Bin Laden never did find a new hiding place, however. He was killed, along with his son, Khalid, his two bodyguards and one of their wives, when U.S. Navy SEALs raided the compound on May 2, 2011. The operation not only rid the world of a terrorist mastermind; it recovered some 470,000 computer files from a trove of ten hard drives, five computers and around one hundred thumb drives and disks.

To understand the man who directed the attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, and set the course of American foreign policy for two decades to follow, there is no better resource than these documents—thousands of pages of his private letters and secret memos. Released in full only at the end of 2017, the files reside on the website of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Among them is a handwritten journal, kept by two of bin Laden’s daughters, that records the last few weeks of his life. Its script is difficult to decipher, so it has previously received scant attention from journalists and researchers. But together with the other Abbottabad documents, it helps to clear up some important mysteries about bin Laden and al Qaeda.

Perplexed by the Arab Spring. During early 2011, in the weeks before he was killed, bin Laden, then in his mid-fifties, was agitated. History seemed to be passing him by. Uprisings swept the Middle East in what became known as the Arab Spring—events that he believed were the most important in the region in centuries. Yet the hundreds of thousands of protestors who risked their lives to protest in Egypt and Libya were not waving his organization’s banner or echoing its call for violent jihad. They were simply demanding basic human rights. Bin Laden was perplexed as to how to respond.

“Is it going to have a negative impact that this happened without jihad?” one of the bin Ladens asked about the Arab Spring.

Fortunately, his oldest wife, Umm Hamza—“the mother of Hamza”—rejoined him in Pakistan at just this time. Bin Laden regarded Umm Hamza as an intellectual peer. She was eight years his senior, with a Ph.D. in child psychology and a deep knowledge of the Koran, and she had spent a decade under house arrest in Iran, since shortly after the 9/11 attacks. Now bin Laden believed that she could help him solve a problem: The Arab Spring revolutions were largely instigated by liberals. Could he nonetheless present himself as the movement’s leader?

In the weeks before he was killed, bin Laden held almost daily family meetings in the Abbottabad compound to discuss how he should respond to the Arab Spring. These consultations included Umm Hamza and his second oldest wife, Siham. A poet and an intellectual with a Ph.D. in Koranic grammar, Siham often edited bin Laden’s writings. She and Umm Hamza were his indispensable intellectual sounding board.

Bin Laden’s two daughters took notes on the family meetings, which show bin Laden, his older wives and his adult children puzzling over the striking absence from the uprisings of al Qaeda’s ideas and followers. A family member asked bin Laden, “How come there is no mention of al Qaeda?” Bin Laden answered concisely and a tad defensively, “Some analysts do mention al Qaeda.”

Bin Laden complained to his family that he had released a public statement as far back as 2004 urging his followers to “hold Arab rulers accountable” and that his intervention had been ignored. Umm Hamza said, “Maybe your statement is one of the reasons for the Arab Spring uprisings?” But, of course, it was not. Even bin Laden’s family members were dimly aware of the fact. One of them observed of the Arab Spring’s largely peaceful revolutions, “Is it going to have a negative impact that this happened without jihad?”

On March 10, 2011, bin Laden prompted his older wives and two adult daughters for their insights: “I would like to know your comments on what you saw on the news that you were watching this afternoon,” he said. Bin Laden’s kitchen cabinet told him that he needed to make a big speech for public release. The family firmly believed that bin Laden’s words could change the trajectory of the Arab Spring.

An apology to Muslims. As part of his public outreach, bin Laden was seriously considering releasing some kind of apology on behalf of al Qaeda and its allies. Not an apology, of course, to the hated Americans. Rather, bin Laden was acutely conscious that since 9/11, groups allied with al Qaeda—for example, al Qaeda in Iraq, al Shabaab in Somalia and the Taliban in Pakistan—had killed many thousands of Muslim civilians and that these exploits had undercut the notion that al Qaeda was fighting a holy war on behalf of all Muslims.

Now bin Laden thought to reposition al Qaeda in the Islamic world as an organization that did not wantonly kill Muslim civilians. He wrote to a top lieutenant saying that he planned to issue a statement in which he would discuss “starting a new phase to correct the mistakes we made.” So badly tarnished had the brand become in bin Laden’s mind that he even considered changing the group’s name. He was seeking a kinder, gentler al Qaeda.

Bin Laden’s proposed rebranding did not extend, however, to stopping planning for terrorist attacks against American targets. As the tenth anniversary of 9/11 approached, bin Laden was eager to memorialize the occasion with another spectacular strike. He told his lieutenants that he wanted “effective operations whose impact, God willing, is bigger than that of 9/11.” He explained that killing President Barack Obama was a high priority, but he also had General David Petraeus, at that time the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, in his sights. Bin Laden told his team not to bother with plots against Vice President Joe Biden, whom he considered “totally unprepared” for the post of president.

Friends and foes: Pakistan, the Taliban, Iran. Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad was not far from Pakistan’s equivalent of West Point. For this reason among others, many observers surmised that bin Laden must have received some support from Pakistani officials or military officers.

Yet the thousands of pages of documents recovered from bin Laden’s compound contain nothing to back up the idea that bin Laden was protected by Pakistani officials or that he was in communication with them. Quite the reverse: The documents describe the Pakistani army as “apostates” and bemoan “the intense Pakistani pressure on us.” They also include plans for attacks against Pakistani military targets.

Al Qaeda’s leaders did contemplate negotiating a deal with the Pakistani government during the summer of 2010. Representatives of bin Laden’s group reached out to leaders of the Pakistani Taliban, who maintained contacts with Pakistan’s military intelligence service, to see if they could negotiate a ceasefire with the Pakistani government. But these negotiations fizzled without yielding a truce.

“The Iranians are not to be trusted,” bin Laden wrote to a top deputy while several of his family members were in Iran under house arrest.

Relations with the Taliban in Afghanistan, on the other hand, remained close. Apologists for the Taliban claim that the group long ago spurned al Qaeda—a premise crucial to the protracted peace talks with the U.S., which required the Afghan militants to reject al Qaeda in return for a complete withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan.

But the Abbottabad documents make clear that al Qaeda and the Taliban had no intention of severing their alliance. In fact, al Qaeda maintained friendly relations with the Taliban and cooperated with them on military operations and funding. According to the documents, bin Laden’s group kidnapped an Afghan diplomat in Pakistan, released him for five million dollars in ransom and then, in 2010, paid a branch of the Taliban known as the Haqqani Network “a large amount” of that money. One of the network’s leaders, Sirajuddin Haqqani, is now the number two leader of the Taliban.

The Abbottabad documents also help to clarify al Qaeda’s murky relationship with the Iranian government. Some al Qaeda leaders and bin Laden family members, such as Umm Hamza, lived under house arrest in Iran for a decade after 9/11. The documents contain no evidence to suggest that al Qaeda and Iran ever cooperated on any attacks. Instead they show bin Laden’s intense distrust of the Iranian regime and record some incidents that served to stoke it.

For example, according to a memo that an al Qaeda member sent to bin Laden, Iranian Special Forces dressed in black and wearing masks stormed the detention center in Iran where some bin Laden family members and al Qaeda leaders were being held on March 5, 2010. The soldiers beat the detainees, including members of bin Laden’s group. Around this time bin Laden wrote to a top deputy that “the Iranians are not to be trusted.”

Still in charge but unaware of strategic failure. After the initial U.S. incursion into Afghanistan, many in the news media and intelligence services imagined that bin Laden was living isolated in a remote cave, cut off from the lieutenants who ran al Qaeda offshoots in his name. The Abbottabad documents instead show that even in the final weeks of his life, al Qaeda’s leader was still managing his organization.

Bin Laden was deeply involved in important personnel decisions and provided strategic advice to his followers in the Middle East and Africa. In 2010, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula nominated a Yemeni-American cleric, Anwar al-Awlaki, as a possible new leader, but bin Laden nixed the appointment. Leaders of al Qaeda in Yemen suggested establishing an “Islamic State” in Yemen. In an undated memo, bin Laden told them the moment wasn’t ripe, and they acceded to his wishes. In a letter he wrote on August 7, 2010, bin Laden urged the Somali terrorist group al Shabaab not to publicly identify itself as part of al Qaeda, and the group complied.

For all his micromanagement, the bin Laden who emerges from the Abbottabad documents is a leader with no awareness that his signature accomplishment, the 9/11 attacks, had spectacularly backfired. Bin Laden made the common mistake of coming to believe his own propaganda: in his case, that the U.S. was a “paper tiger,” that it would pull out of the Middle East following the 9/11 attacks, and that then its client regimes, such as the one in Saudi Arabia, would fall like dominos.

In fact, following 9/11, the U.S. waged military campaigns against jihadist terrorist groups in seven Muslim countries—Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. Though these campaigns were certainly costly—to date, some six trillion dollars, more than 7,000 American lives and hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths—they are far from the retreat that bin Laden anticipated. After 9/11, American bases proliferated throughout the region, while al Qaeda—“the Base” in Arabic—lost the best base it ever had in Afghanistan.

Only now, two decades after 9/11, is the U.S. finally pulling out of Afghanistan and to some degree Iraq—countries where bin Laden never envisaged a U.S. presence. At the same time, the U.S. continues to maintain substantial bases in countries such as Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. The 9/11 attacks didn’t end the U.S. presence in the Middle East; they greatly amplified it.

Osama bin Laden was one of the few individuals who can be said to have changed the course of history, but the results were not at all what he had hoped for. In 2011, as the tenth anniversary of 9/11 approached, his overriding goal was to carry out another spectacular terrorist attack against the U.S. He died knowing that he had failed.

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...