The Nobel Peace Prize has dogged Abiy Ahmed since he went to a war a year ago, stoking the outrage of critics who viewed the 2019 prize awarded to Ethiopia’s prime minister as a terrible mistake.

But this week Mr. Abiy went a step further when he declared that he was heading to the battlefront himself to lead the army as it tries to stave off rebels advancing on the capital.

On Friday, state media reported that he was in the northeastern region of Afar — where the rebels are trying to cut off a major supply route — and aired footage of him wearing khakis and sunglasses. Appearing relaxed and confident, Mr. Abiy told a television interviewer: “We won’t flinch till we bury the enemy and ensure Ethiopia’s freedom.”

His show of bravado only fueled the growing sense of urgency over a war that has displaced two million Ethiopians, driven at least 400,000 into famine-like conditions and now threatens to tear Africa’s second-most populous country apart.

Foreigners are leaving in droves, and an American-led diplomatic scramble to broker a peace has stalled. Ethnic Tigrayan rebels, who started their march on Addis Ababa from northern Ethiopia in July, say they are now 120 miles by road from the capital.

As fears grow that the capital’s airport — one of the busiest in Africa — could soon close, two U.S. military officials confirmed a report that C-17 military cargo planes have been positioned in neighboring Djibouti, in case an evacuation of American citizens becomes necessary.

The officials stressed that was not likely to happen over the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. But beyond that, few were willing to predict what might come next.

Although his military has suffered a string of humiliating defeats, Mr. Abiy retains a deep well of public support. His defiance was publicly backed on Wednesday by an Ethiopian national hero, the two-time Olympic gold medalist Haile Gebrselassie, who announced that he, too, would head to the front lines.

Mr. Gebrselaisse is 48. But many younger Ethiopians are backing Mr. Abiy’s campaign, offering to defend Addis Ababa or join the battle in the north — even if they have never fired a weapon.

“I am following the prime minister,” said Sintayehu Mulgeta, 28, a taxi driver who has joined a newly formed vigilante group that prowls the streets of Addis Ababa at night, armed with sticks, hunting for suspected rebels.

Mr. Sintayehu blamed the Tigray People’s Liberation Front — which dominated Ethiopia for 27 years until 2018, and controls the rebels now approaching the capital — for the death of his cousin during a political protest in 2016.

“They have my cousin’s blood on their hands,” he said. “I never want them back again.”

The belligerent posture reflected the jarring turn that Mr. Abiy has taken from just two years ago, when he stood on a stage in the Norwegian capital Oslo to accept the Nobel Peace Prize. “War is the epitome of hell,” Mr. Abiy said then.

In the past year, however, references to infernal suffering in Ethiopia have mostly focused on Tigray, the northern region where Mr. Abiy’s forces and their allies from Eritrea and neighboring Amhara region have faced allegations of massacres, sexual violence and ethnic cleansing.

The Tigrayans have also faced allegations of abuse, albeit on a smaller scale.

The Biden administration is leading a diplomatic effort to halt the fighting and prevent the collapse of a key U.S. security partner in the Horn of Africa. Visiting Kenya last week, Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken discussed the crisis with President Uhuru Kenyatta.

But the Tigrayans have continued to push south, this week claiming to be outside Debre Sina — a key town, perched on a high ridge, about 120 miles from Addis Ababa by road.

The Ethiopian government has vacillated between pillorying the foreign media for overplaying its losses, and offering dramatic gestures that seem to indicate vulnerability as much as strength.

Before heading to the battlefield this week, Mr. Abiy said it was a time when “martyrdom is needed.”

On Wednesday, his government expelled four Irish diplomats — out of six in the country — over Ireland’s outspoken criticism of Mr. Abiy’s actions. They joined a list of foreign journalists, aid workers and senior United Nations officials who have been forced out of Ethiopia since the summer, when the tide of the war started to turn.

Security forces have engaged in a fierce roundup of ethnic Tigrayans that has seen thousands arrested, many crammed into makeshift detention centers.

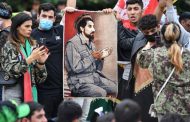

In daily recruitment ceremonies, older Ethiopians listen intently to speeches denouncing the Tigrayan “junta,” as the T.P.L.F. is called, as younger men and women volunteer to head for the front lines.

“I don’t want to see the junta in power again,” said Tilahun Mamo, 32, a parking lot attendant who leads a group of 30 vigilantes in the city’s Bole neighborhood, and is waiting to be called up for the war.

Deep-seated fears of Tigrayan rule undergird some of Mr. Abiy’s support. During its 27 years of political dominance, the T.P.L.F. brought economic progress to Ethiopia but also rigged elections, jailed and tortured critics and smothered the free press.

But analysts say that Mr. Abiy has also engaged in a concerted campaign of vilifying Tigrayans, which senior U.N. officials have warned could descend into ethnic or even genocidal violence.

“Why would I sit back and wait for the terrorists to come take my city?” said Dereje Tegenu, a 42-year-old security guard and member of a vigilante group in Addis Ababa. “I will go fight them.”

The ethnic fault lines are most vivid among the Oromo, who account for about one-third of Ethiopia’s 110 million people. Although Mr. Abiy, whose father is Oromo, rode to power in 2018 on a wave of street protests led by angry young Oromos, many in that movement now say that he betrayed their cause.

Some have taken up arms against him, most notably through the Oromo Liberation Army that has joined with the Tigrayans in the march on Addis.

In a phone interview, Jaal Marroo, the leader of the Oromo group, dismissed Mr. Abiy’s pledge to go into battle as “a joke,” and predicted that the country was “heading for mayhem.”

“The government is frustrated, using human waves to play their final card — mobilizing ethnic groups,” he said.

Oromo political prisoners say their lives are in danger. Jawar Mohammed and Bekele Gerba, two prominent Oromo leaders jailed last year, issued a statement through their families this week saying that they fear their prison guards are trying to kill them.

This week, France and Germany joined a list of Western countries urging their citizens to leave Ethiopia as soon as possible, while regular flights are still operating. The U.S. Embassy has ordered all nonessential personnel to leave, and this week warned of the potential for unspecified “terrorist attacks” in Ethiopia.

At a news conference on Thursday, an Ethiopian government spokesman denounced the American warning as “false information.”

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...