Nearly 100 candidates declared they were running for president, a few of them among the most prominent in Libyan politics. More than a third of Libyans registered to vote, and most signaled their intention to cast ballots.

Western leaders and United Nations officials had thrown their support behind the election, one they said represented the best hope of reunifying and pacifying a country still largely divided in two and dazed from nearly a decade of internecine fighting.

For more than a year now, Libya has been hurtling toward a long-awaited presidential election scheduled for Friday, the 70th anniversary of the country’s independence. But with just a few days to go, the vote looks virtually sure to be postponed as questions swirl about the legitimacy of major candidates and the election’s legal basis.

Amid the uncertainty, the national election commission dissolved the committees that had been preparing for the vote, essentially conceding that it would not occur on schedule. For now, it was the closest thing Libyans were likely to get to a formal announcement, given all parties’ reluctance to make such a declaration and take the blame.

A delay poses the risk that the oil-rich North African nation will again descend into the fragmentation and violence that have marked the decade since the dictator Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi was toppled and killed in the 2011 revolution.

Though no one has formally announced a change in plans, government officials, diplomats and Libyan voters alike have acknowledged that voting on Friday would be impossible. The question now is not only when a vote might take place, but whether a postponed election would be any less brittle — and who would control Libya in the interim.

“There will definitely be a conflict,” said Emadeddin Badi, a senior fellow and Libya analyst at the Atlantic Council who was in Tripoli on Tuesday, “one that could potentially devolve into a broader war.”

On Tuesday, tanks and armed militiamen deployed in some parts of Tripoli, closing the road to the presidential palace in a show of force that led to no violence, but raised the tension level.

The election of a new president is regarded as the key to begin evicting the armies of foreign fighters brought in over the past years to wage civil conflicts, to start building Libya’s multiple militias into a single national army, and to reunifying government institutions.

So far, predictions of large-scale violence surrounding the election have not materialized, although militias in Tripoli last week surrounded government buildings, clashes broke out in the south and militia fighters shut down two major oil pipelines on Monday, denting oil production.

International mediators may still be able to salvage the election with a minor postponement of a month or so, though analysts and diplomats said this was unlikely.

Stephanie Williams, the United Nations diplomat who brokered the peace process that led to the election agreement, recently returned as the U.N.’s top envoy to Libya and has been crisscrossing the country in hopes of winning a best-case-scenario postponement of weeks, not months or — worst of all — indefinitely.

“It’s never too late for international mediation,” she said on the One Decision global affairs podcast earlier this month.

The United States ambassador to Libya, Richard Norland, visited Tripoli on Monday to tour a polling station and meet with civil society workers who had been preparing for the vote.

“The United States continues to support the vast majority of Libyans who want elections and to cast a vote for their country’s future,” he said in a statement. “We are working to be partners in this process, allowing Libyans to make the choice.”

But analysts and a senior diplomat acknowledged that the international drive toward a Dec. 24 election had overlooked crucial issues, which ultimately scuppered the vote.

The three front-runners were all highly polarizing, raising fears that if one of them won, others would bitterly, and perhaps violently, contest the result.

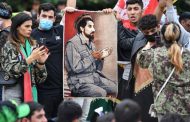

One of the three, Seif al-Islam el-Qaddafi, is the son of the former dictator, who was killed by rebels in 2011. Another, the strongman Khalifa Hifter, who controls eastern Libya, waged a military campaign from 2019 to 2020 to try to wrest the capital, Tripoli, out of the hands of an internationally recognized government.

The third front-runner is Abdul Hamid Dbeiba, the interim prime minister in the current government who has been accused by other candidates of misusing public funds to win voter support by shelling out cash grants to young Libyans.

All three face challenges to the legitimacy of their candidacies.

Mr. el-Qaddafi is charged with war crimes in the International Criminal Court stemming from his attempts to help his father put down the 2011 revolution. Mr. Dbeiba did not step down from his post in time to run, as required by electoral law. Diplomats said both men had pressured courts in friendly jurisdictions to rule that they were eligible to run.

The election also lacked a constitutional basis and rested on legal quicksand, experts said.

Since the revolution, Libya has been divided in two. The western side has an internationally recognized government based in the Tripoli, while the eastern side, Mr. Hifter’s base of power, has a rival government.

An election law that was rushed through Libya’s eastern parliamentary body, but not the western one, was roundly criticized across Libya and amended multiple times, in part to allow Mr. Hifter to run.

Even had the election gone forward, there was never much chance that one elected leader could have cured all of Libya’s ills. Instead, some of the country’s underlying issues must be resolved first to empower a newly elected president to work effectively, analysts say.

“I think that this is all wishful thinking,” Hanan Salah, the Libya director for Human Rights Watch, said at a panel discussion last week.

She noted that the militias continue to operate with impunity, even government-linked ones, and that there had been outbreaks of violence tied to the election. Libya is so fragmented that some candidates could not even set foot in certain parts of the country to campaign.

“Our concern is the lack of rule of law, justice and accountability mean no free and fair elections are possible in the current environment,” Ms. Salah said.

Yet millions of Libyans expressed a commitment to voting, whether for a better future or just to try to knock out controversial candidates.

“After seven years of civil conflict and dysfunctional politics, Libyans are eager to vote,” said Mary Fitzgerald, a Libya specialist and nonresident scholar at the Middle East Institute in Washington.

More than 2.4 million out of 2.8 million registered voters collected their voting cards over the past month, she noted. “That’s a clear sign that there is tremendous enthusiasm for these elections — whenever they may happen — and a huge appetite for change,” Ms. Fitzgerald said.

But with Dec. 24 most likely to come and go without a vote, some Libyan politicians have already been jockeying for control of the country after Friday, two senior diplomats said.

On Tuesday, several of the most prominent presidential candidates met with Mr. Hifter in Benghazi, the de facto capital of eastern Libya, forming an alliance that might seek to fill any post-Dec. 24 power vacuum. They appeared to be trying to paint themselves as a credible alternative to the current government, which these politicians argue will lose legitimacy after Dec. 24.

“It’s a power grab disguised as deliverance,” said Mr. Badi, the Atlantic Council analyst.

There does not appear to be any single candidate who could command broad enough support to lead a new unity government, diplomats and analysts said.

If the election is not held soon, a senior Western diplomat said, Libya runs the risk of derailing progress toward reunification, with Mr. Dbeiba in charge of western Libya and someone else running a de facto government in the east.

Kamal Mohammed, 39, a clothing store salesman from Tripoli, said he hoped the election would eventually occur, and that it was worth the effort.

“We’re worried, but we can’t lose hope,” he said. “We feel that this is the last step for a better future. The ballot box is the best solution — the people have to choose who their leader is.”

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...