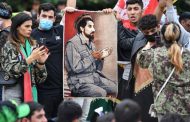

Across Ethiopia, thousands of men and women are quitting their jobs to enlist with the country’s armed forces, as rebels from the Tigray People’s Liberation Front advance toward the capital, fanning fears that a simmering conflict will spiral into full-blown civil war.

Teachers, shopkeepers and students have swelled their ranks. Former soldiers have come out of retirement. Olympic long-distance legends Haile Gebrselassie and Feyisa Lilesa have thrown their support behind Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who has been pictured directing the campaign against the TPLF from the front lines.

“Saving my country is my highest priority right now,” said Bilet Alamrew, who was a librarian at Debre Berhan University in the north of Ethiopia before joining a pro-government militia. “It is the main reason I left my job to join the army.”

It is a similar situation across the rebel lines. Ethnic Tigrayans have flocked to join the TPLF after government forces swept through the mountainous northern region earlier this year.

The influx of raw recruits on each side has many Ethiopians worrying that the conflict is about to enter a dangerous new phase. Untrained militias will likely be harder to control, potentially fanning ethnic strife, rights groups and security consultants say. A full-blown conflict risks repeating the turmoil that afflicted the country in the 1980s. The yearlong fighting has already displaced millions of people from their homes, with 400,000 living in famine-like conditions, the United Nations has warned.

“The blurring of lines between combatant and civilian increases the risk of human rights abuses and the difficulty in holding perpetrators to account,” said Edward Hobey-Hamser, Africa analyst at risk consulting firm Verisk Maplecroft. “That this is happening in a country with deep ethnic cleavages is particularly ominous.”

The TPLF dominated Ethiopia’s government for decades after displacing a Marxist regime in the 1990s, overseeing a rapid period of economic growth and foreign investment. But after Mr. Ahmed took office in 2018, he began whittling away its influence.

Fighting has raged across northern Ethiopia since Mr. Ahmed ordered an offensive in response to an attack by TPLF forces on a government military base in November 2020. The conflict has added to the instability in the Horn of Africa, a strategic region overlooking the entry to the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Neighboring Eritrea has sided with the Ethiopian government, but Egypt, wary of Ethiopia’s plans to choke off the waters of the Nile with a vast hydropower dam, has long sought to destabilize it.

Some supporters of the TPLF were tortured, sexually abused and killed by Ethiopian forces and their Eritrean allies, according to rights groups. The U.S., U.K. and other Western nations have warned their citizens to leave Ethiopia immediately, as rebels advance south toward Addis Ababa, prompting the government to complain that it has been abandoned by the international community.

Mr. Ahmed has called for ordinary Ethiopians to rally around his government’s armed forces—many of whose officers are Tigrayan—instead.

Some of the country’s biggest names are now supporting the war effort. Mr. Gebrselassie, a double Olympic gold medal winner, has been vocal in his backing for Mr. Ahmed.

So, too, has Mr. Lilesa, who became famous after crossing his arms across his head as if they were shackled as he crossed the finish line to take the silver medal in the men’s marathon at the 2016 Rio Olympics. He spent years in exile after the gesture, which was intended to draw attention to the former TPLF-led government’s crackdown on pro-democracy protesters.

Last week, he traveled to the front line, around 250 miles northeast of Addis Ababa, where Mr. Ahmed is attempting to halt the rebel advance.

“There is a leader directing the war from the front,” Mr. Lilesa said. “I am not leaving my country, rather I will fight shoulder-to-shoulder with the rest.”

The government has claimed some success in slowing the TPLF’s gains, but there are fears that a rebel attack on Addis Ababa might be imminent.

Some 200,000 youths have joined vigilante groups to defend the capital, according to its mayor, Adanch Abebie. Others, armed with sticks, patrol the streets each evening, searching vehicles for suspected rebels and weapons.

U.N. investigators and rights groups such as Amnesty International have accused vigilantes of participating in a brutal crackdown against ethnic Tigrayans that includes mass arrests, kidnappings, and in some instances, targeted executions. A spokeswoman for Mr. Ahmed described the allegations as “panic-mongering.”

Volunteers are a useful asset for both sides, however. Demobilized army units have been fighting alongside government troops in the Afar region in recent weeks, helping the military to reverse battlefield setbacks suffered since July. Last week, government troops recaptured the town of Chifra, forestalling a threat to cut off the highway that links landlocked Ethiopia to the coast. In recent days, government forces have recaptured two other strategic towns in the Amhara region, north of Addis Ababa.

Some volunteer fighters like Worku Alemenew, a 52-year old former army captain, have fighting experience. He battled against TPLF guerrilla fighters through the 1980s until 1991.

“My colleagues and I have solid military skills. We can be of help now more than ever,” Mr. Alemenew said in Addis Ababa, as he prepared to go to the front line.

Another soldier, identifying himself as Bennie, took a different route. After retiring from the military in 2000, he ran a textiles shop in the Tigrayan regional capital, Mekelle. When the war broke out last year, he said his shop was looted by government troops. He decided to join the TPLF fighters, training new recruits in artillery and other weaponry in the northern mountains.

“The recruits are very brave and determined,” he said. “Many joined after suffering abuses from Eritrean and government soldiers.”

TPLF forces, reinforced by militias, last month staged a raid on the strategic town of Debre Sina, 120 miles from Addis Ababa, sending government forces into retreat. Rebel leaders say their battlefield advances come from a combination of new recruits and superior training from experienced commanders who, until comparatively recently, held senior roles in the Ethiopian armed forces.

U.S. diplomats who have spent months trying to broker a truce appear to be losing patience. Last month, Jeffrey Feltman, the U.S. envoy to the region, said that Washington’s efforts were being outpaced by the “alarming developments on the ground.”

Mr. Ahmed, a longtime U.S. ally who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for brokering a truce to end the three-decade conflict with Eritrea, has continued to focus on taking the battle to the TPLF.

“Our remaining task is to rout the enemy and destroy them,” Mr. Ahmed told state television from the front lines last week, dressed in combat fatigues. His opponents, he said, “should know they have been defeated and surrender.”

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...