By: Sara Hazem

“From what age did you start flowing through the villages?

And by whose hand do you bless the cities?

Did you descend from the heavens, or were you sprung

From the lofty gardens, flowing like sparkling streams?

And through whose eye, cloud, or flood

Do you overflow and flood the lands?”

These are the questions posed by the Prince of Poets, Ahmed Shawqi, and immortalized in song by Umm Kulthum in praise of the eternal Nile, which has linked earthly life with the afterlife in the beliefs of ancient Egyptians for millennia. As a result, homes, palaces, and temples of the gods were often built on the eastern bank of the Nile, while tombs and funerary temples were located on the western bank.

In his book Egypt and the Nile: Between History and Folklore, Dr. Amr Abdel Aziz affirms that thinkers throughout history have been captivated by the Nile, constantly describing and studying its sources, basin, and mouth. This fascination is natural, as anyone who has lived in Egypt, interacted with its people, visited, or neighbored it knows that the Nile is the source of Egypt’s wealth and prosperity. It is the fundamental pillar upon which early Egyptian civilization was built, a civilization that has impacted the entire world.

It is no surprise that the Nile has been of paramount interest to Egyptians and others since ancient times, and no river in the world has had such a profound influence on a region and its inhabitants as the Nile. In the Book of the Dead, the ancient Egyptian would swear, “I have not polluted the river’s water,” demonstrating the deep reverence and care they held for this life-giving artery of Egypt.

The Great River

The ancient Egyptians called the Nile “Atro Aa” or “The Great River” because it was the god of fertility and abundance, ensuring protection from famine and drought. The term “Nile” itself originates from the Greek word “Neilos.” The Nile’s primary deity was “Hapy,” depicted as a full-chested, full-bellied man, symbolizing the river’s bountiful gifts. Additionally, there was a god of the flood, “Khnum,” worshiped in Aswan. As the god of creation, Khnum was also associated with the flood, which the ancient Egyptians believed was responsible for creating the fertile Egyptian land.

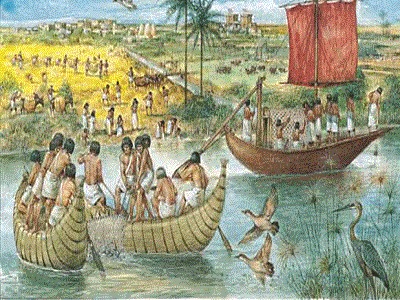

The exploration of the Nile began when ancient Egyptians transitioned to agriculture. Although their knowledge of the river’s upper reaches was limited, they quickly connected with the people and lands inhabiting the Nile Valley to Egypt’s south, continuing their efforts to uncover the river’s mysteries.

Due to their lack of knowledge about the Nile’s sources in Central Africa, the ancient Egyptians believed that the river originated from a subterranean cave on the island of Biga in Aswan. Greek historian Herodotus noted that the chief priest of the goddess Neith in Sais mentioned the river emerging between two mountains on that island, named “Krophi” and “Mophi.” The river, according to this account, sprang from between these two peaks. In the Philae Temple in Aswan, the god Hapy is depicted inside a cave, with a serpent coiled around him, symbolizing the Nile’s flow from a narrow opening between the snake’s tail and mouth.

Ancient Projects

The ancient Egyptians were diligent in making the most of the Nile’s resources, implementing major projects during their time. One of these projects was turning the city of Memphis (now Mit Rahina) into a quasi-island to protect it, a feat achieved by the first pharaoh of Egyptian history, King Menes.

Additionally, the largest agricultural project in Egypt’s history was initiated, reclaiming 100,000 acres of land in what is now Faiyum. This project was undertaken by the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom in the 20th century BCE, diverting excess floodwater into Lake Qarun through a channel still known today as “Bahr Youssef.” The ancient Egyptians also carved a canal through the rocks of the first cataract east of Sehel Island in Aswan to facilitate the passage of boats. This canal was named after its creator, King Senusret III, and carried the title “Beautiful are the Ways of King Khakheperre.”

The Flood

In ancient Egypt, the most significant event linked to the Nile was the arrival of the annual flood, which the Egyptians marked as the start of their calendar year. The ancient Egyptians divided their year based on the Nile’s behavior, with the first season being the flood season. Once the floodwaters receded, the agricultural season began, followed by the harvest season, which completed the annual cycle.

According to Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass, the ancient Egyptians closely monitored the river, eagerly awaiting the months of the flood signaled by the appearance of the star Sirius in the sky. As the floodwaters arrived, the agricultural year would commence, and they devised the Nilometer to measure the water level and anticipate the bounty flowing from the south.

The Nile’s Loyalty

For about seven thousand years, the Egyptians have celebrated the festival of “Wafaa El-Nil” (The Nile’s Loyalty), one of Egypt’s oldest historical festivals, traditionally held in August (the month of Boona). The term “Wafaa El-Nil” refers to the Nile’s loyalty in delivering the Egyptians bountiful water and silt.

The flood lived on in the collective memory of the Egyptian people, who continued to celebrate it annually through the ages, even during periods of foreign rule. The festival of “Wafaa El-Nil” remained a profound expression of the Egyptian people’s bond with the Nile, deepening their connection to it.

The Bride of the Nile

As the Nile spread life along its banks, it also inspired various myths and legends, which varied depending on the era and location. One such legend is the story of the “Bride of the Nile,” which tells of the ancient Egyptians offering a beautiful maiden to the god Hapy during his festival. The girl, adorned in finery, was thrown into the Nile as an offering to the god and would marry him in the afterlife. In one version of the story, when no girls were left, the king’s daughter was the only choice. However, her maid hid her and instead threw a wooden effigy into the river, fooling everyone. The maid then returned the girl to her father, who had fallen gravely ill from sorrow at her supposed death. Thus, the tradition of throwing a wooden effigy, known as the “Bride of the Nile,” into the river was born.

However, Egyptologists agree that there is no historical evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians sacrificed a human “Bride of the Nile” during the festival. Human sacrifices were never practiced by the ancient Egyptians, and any offerings made were either animal or symbolic. In her book The Nile in Popular Literature, writer Ne’mat Ahmed Fouad emphasizes that the story of the Bride of the Nile has no historical basis, except for the account given by the historian Plutarch, who wrote that King Egyptus sacrificed his daughter to the Nile upon the advice of priests to avert disasters befalling the land, later regretting the act and throwing himself into the river after her.

French researcher Paul Lange, who dedicated his studies to the Bride of the Nile myth, concluded that the ancient Egyptians did not throw a living bride into the river. Instead, the Egyptians celebrated by offering a fish known as “The Atem,” whose skeleton resembles a human’s. Because of this similarity, scholars referred to it as the “Bride/Lady of the Sea.”

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...