Iraqis voted in a parliamentary election that could shape the future for U.S. forces still based there and indicate how Baghdad will navigate a broader geopolitical power struggle between Washington and Tehran.

Polls closed in the evening on schedule in Sunday’s election, which was brought forward as a concession to a protest movement that began in 2019. The election was dominated by the issues that triggered the upswell of dissent: an economic crisis and endemic corruption.

Election officials have said results will be announced within 24 hours of the polls closing, though delays are widely anticipated. In the last vote, in 2018, results were announced a week later.

But the ballot was also colored by the struggle between Iran-backed militias and the U.S., which has about 2,500 troops in the country and is under growing political pressure to leave Iraq after its exit from Afghanistan.

For much of this year the country was caught in a spiral of violence between Iranian-backed paramilitary groups and the U.S. military, which has launched airstrikes in response to rocket and drone attacks on its bases. President Biden agreed to pull U.S. combat troops out of Iraq by the end of the year, but most of the 2,500 soldiers will remain in the country in training and support roles.

The conflict is adding to the pervading tension, worsened further by crumbling government services. Long power outages plagued the country for much of the summer at a time when Iraqis endure some of the highest temperatures on Earth.

Iraq’s political system, in which multiple parties each vie for the votes of various sectarian groups, means that the election is unlikely to deliver a decisive result. Instead, weeks or months of negotiations toward the formation of a government are likely to follow.

An array of Sunni and Shiite Muslim Arab parties competed, along with a separate group of parties seeking the ethnic Kurdish vote concentrated in the country’s north.

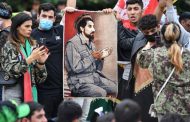

Opinion polls projected that a bloc led by the populist Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr would win the largest share of seats in parliament, an outcome that would once again make him kingmaker in negotiations to form a government.

Mr. Sadr’s bloc, in an alliance with Iraqi communists, won the largest share of seats in Iraq’s most recent election in 2018. A onetime rebel leader after the U.S. invasion and champion of Iraq’s Shiites living in urban poverty, he is against the presence of American troops and is also an opponent of Iran’s growing influence, setting him apart from some other Shiite politicians. He has also spoken out against some attacks on U.S. interests in the country.

A poll from the Rafidain Center for Dialogue, an Iraqi think tank, projected Mr. Sadr’s bloc to win 42 seats, down from 54 in the 2018 election.

The survey predicted a low voter turnout of 38% to 42%, reflecting widespread political disenchantment.

“Protesters and young people don’t think that they can get any accountability or justice from the current crop of politicians,” said Sajad Jiyad, a Baghdad-based political analyst with the Century Foundation, an American think tank.

“They don’t think they can achieve results through the ballot box,” he said.

Iraq’s current leader, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who was appointed last year in the aftermath of the protests, didn’t run in the election. He instead appears to be positioning himself to remain in place through a postelection deal among the country’s rival political forces, analysts say. But he faces strong opposition from Iranian-backed groups who accuse him of being involved in the 2020 U.S. killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi militia leader Abu Mahdi al-Mohandes.

Qais al-Khazali, head of the Asaib Ahl al-Haq militia, one of the main groups protesting the presence of U.S. troops, said Iraq needs a new prime minister who is focused on resolving its economic problems, and that these will take priority once American forces withdraw. “Our country is not suffering mainly from political or security issues but from economic ones like lack of infrastructure and lack of jobs,” he said on state television after casting his vote.

One of the largest Iranian-backed militias, the Hezbollah Brigades, was directly running in the election for the first time, fielding a slate of 32 candidates, showing how the paramilitary groups have grown in their political power since playing a key role in the fight against Islamic State in 2014. It urged its supporters to vote, exhorting them on Thursday to “achieve a victory that pleases your martyrs,” and analysts suggest a low turnout could strengthen its hand and that of other militant groups.

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, Iraq’s most important Shiite leader, who met Pope Francis when he traveled to Iraq in March, had urged people to turn out and vote to “prevent corrupt figures from making it to parliament,” as he put it.

The election is also a test for Iraq’s security forces as they work to protect candidates and voters throughout a country that is still battling the remnants of Islamic State and wrestling with the influence of a range of armed groups. Security forces were deployed heavily in Baghdad and other cities on Sunday.

Unidentified gunmen on a motorcycle opened fire at a car transporting a candidate named Sadeer Al Khafaji on Friday, according to a police official. Mr. Khafaji wasn’t hurt in the attack, the official said.

Two police officials said snipers attacked election workers at a polling station near Kirkuk while they were loading ballot boxes onto trucks to take them to a counting center. One police officer was killed and three others injured, while security forces returned fire, securing the ballots.

With many of the same politicians and factions that have jostled for position since the American invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein in 2003 vying for the vote, many Iraqis say they plan to boycott an election they see as designed to buttress the status quo.

“I’m not seeing any hope on the horizon.” said Sabah Khalaf, a 45-year-old government employee in Baghdad, who, speaking before polls closed, said he wouldn’t vote.

Instead, some Iraqis are turning to street protests as a means to force a change in the way the country works. Vast demonstrations erupted in Iraq in 2019, demanding fundamental reforms in a state that consistently ranks as one of the most corrupt in the world and where Iranian-allied militia groups hold increasing political power. Security forces violently repressed the demonstrations, killing more than 600 people, according to the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights.

At least 35 activists have also died in targeted killings since the beginning of the protests, according to the commission, including a researcher, Ihab al-Wazni, whose killing in May triggered another wave of protests.

The protest movement has birthed a small group of parties that also sought seats in parliament.

“We are determined to focus on Iraq’s integrity,” said Mushreq Al-Fraiji, the leader of a party called Demonstrating for My Rights.

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...