Surafel Alamo immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia in 2006 at the age of 12 with his father and a sister. The Israeli authorities said two older sisters, who were over 18 at the time, would follow in a month or two. They have been waiting in a camp for would-be emigrants in Ethiopia ever since.

Now, with Tigrayan rebel forces pressing southward toward the capital, Addis Ababa, where the Ethiopian government has declared a state of emergency, Ethiopian-Israelis like Mr. Alamo are growing nervous about the safety of their relatives. They are pressuring the Israeli government to extricate thousands of them from the dangers of the civil war and to end the yearslong trauma of split families once and for all.

But the fate of the remnants of the community has become bogged down in rancorous disagreements over the urgency of the situation in Ethiopia, the legitimacy of their claims, the numbers of those eligible for Israeli citizenship and accusations of racism.

Israel has vaunted its rescues of Ethiopian Jews in the past. The last major operation, in 1991, brought in 14,000 of them from camps in Gondar Province and Addis Ababa in a secret airlift over 36 hours. Officials say that about 5,000 Ethiopians with Jewish lineage are now slated for immigration, but that there could be thousands more.

Opponents of further family reunifications say the original Jews of Ethiopia and their descendants, many of whom were converted to Christianity by European missionaries in the late 18th century, already left long ago. Those now filling the camps are mostly relatives of converts with little or no connection to Judaism, they say, and once they immigrate the relatives of the relatives will want to come, turning the immigration from Ethiopia into a never-ending saga.

Many Ethiopian-Israelis and their supporters say that large numbers of those who converted to Christianity did so under duress, and that they remained in separate communities in Ethiopia and maintained their traditions. They accuse their critics and the Israeli government of racism and discrimination, actively encouraging Jewish immigration, known in Hebrew as Aliyah, from wealthier countries.

“They are Jews, yes, Black Jews,” said Mr. Alamo, 26, who has served as a paratrooper in the Israeli Army and now studies political science at the University of Haifa. “Israel must bring them.”

Mr. Alamo’s mother died before she could get to Israel; his father died there. Mr. Alamo’s last contact with the sisters in Ethiopia, now 35 and 45, was a month ago, he said, adding that the war had made communication difficult. After years of sending papers to the Israel’s Interior Ministry on their behalf, he said their status was still not clear.

“If I’m here, I’m a Jew, right?” he said. “So are they.”

The question of “who is a Jew” has long been entangled with Israel’s immigration policy and relations with the diaspora. The ancient and complex history of Ethiopian Jewry has posed a particular challenge. The original Jews of Ethiopia, known as “Beta Israel,” or House of Israel, are, according to some traditions, descendants of the lost tribe of Dan. Israel officially recognized their Judaism, making them eligible for automatic citizenship, only in the 1970s.

Once the Beta Israel had been airlifted, the Israeli government was pressured into bringing in the Christian converts who were waiting in the camps. Known as Falash Mura, a pejorative in Ethiopia, the Israeli authorities referred to them as “Zera Israel,” or the seed of Israel.

By now a majority of the roughly 150,000 Israelis of Ethiopian descent, who make up about two percent of the population, are members of the Zera Israel community, according to experts.

Israel has declared the mission of moving the remnants of Ethiopian Jewry complete several times, most recently in 2013. But two years later, again under pressure, the government said it had resolved to bring “the last of the members of the communities waiting in Addis Ababa and Gondar” to Israel by 2020.

Candidates must be invited by a first degree relative in Israel, have arrived in the camps no later than in 2010 and commit to undergoing a religious conversion to Judaism once in Israel.

Their numbers were estimated then at about 9,000. Four thousand have since arrived, including 2,000 over the past year. This week the government agreed to expedite the transfer of the remaining 5,000, without specifying any clear time frame.

But the number of those waiting in the camps is now said to be at least 8,000, at least in part because families have expanded during the years of waiting.

Further confounding the situation, Israel’s National Security Council has assessed that there is no urgency or need for immediate rescue, even though Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has just pulled the families of its diplomats out of Addis Ababa and has warned Israelis not to travel to Ethiopia.

“You can’t play a double game,” Nachman Shai, Israel’s minister of diaspora affairs, said in an interview, referring to disagreements within the government. “It’s either this or that. Either there is an emergency situation or there isn’t. They need to make their minds up.”

“My position is to bring them, as soon and as many as possible,” he added, “and then say this operation of 40 or 50 years is over.”

Israel’s minister for immigration and integration, Pnina Tamano Shata, herself a member of Beta Israel, has championed the cause of those left behind on behalf of her primary constituency. Israel’s minister of interior, Ayelet Shaked, the country’s conservative gatekeeper, is more circumspect and is reviewing the criteria for Ethiopian immigration.

Another setback came with the emergence in the Israeli news media this week of a murky story about a group of 61 Ethiopians, mostly Tigrayans, who were secretly brought to Israel from Sudan in July. This was done at the behest of a member of the Ethiopian Jewish community in Israel, amid claims that their lives were in danger.

An Interior Ministry document from August reviewed by The New York Times stated that the 61 appear to have no clear family links in Israel nor, in most cases, any connection to Judaism, and that they had not been in danger but had simply exploited the system.

Activists have questioned the timing of the leak, saying it was intended to damage the effort to bring the remnants of Ethiopian Jewry to Israel.

“It’s a spin,” said Uri Perednik, chairman of a non-profit organization called the Struggle for the Aliyah of Ethiopian Jewry. “This group has nothing to do with the communities in Addis Ababa and Gondar.”

Still, the civil war has reopened the debate on the saga of the Ethiopian immigration to Israel.

“There’s no end to it,” said Ben-Dror Yemini, a prominent columnist for Yediot Ahronot, the popular Hebrew daily, who has written critically on the subject, characterizing the continued immigration as fraud. “After this 10,000 there’ll be another 10,000 with first degree relatives, and then more relatives of relatives,” he said in an interview.

Mr. Yemini added that he was giving voice to frustrated members of the original Beta Israel. He described the intentions of those lobbying for the Ethiopians, including American Jewish groups, as well intentioned but misplaced, and the conduct of successive Israeli governments as negligent, saying they repeatedly caved into emotional pleas and protests over the years.

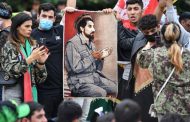

Fresh protests are scheduled for Sunday.

“This Aliyah has always been subject to wars and arguments,” said Aschalo Abebe, 36, a cleaning contractor and social activist who arrived in Israel in 2002. He said he only recently discovered some relatives of his mother who are waiting in the camps and are eligible for immigration, because their grandfather was Jewish.

“I worry day and night,” he said, adding of the government, “They shouldn’t wait for some disaster to happen.”

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...