Over the past 20 months, Israeli intelligence operatives have assassinated Iran’s chief nuclear scientist and triggered major explosions at four Iranian nuclear and missile facilities, hoping to cripple the centrifuges that produce nuclear fuel and delay the day when Tehran’s new government might be able to build a bomb.

But American intelligence officials and international inspectors say the Iranians have quickly gotten the facilities back online — often installing newer machines that can enrich uranium at a far more rapid pace. When a plant that made key centrifuge parts suffered what looked like a crippling explosion in late spring — destroying much of the parts inventory and the cameras and sensors installed by international inspectors — production resumed by late summer.

One senior American official wryly called it Tehran’s Build Back Better plan.

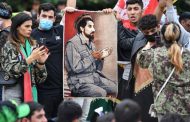

That punch and counterpunch are only part of the escalation in recent months between Iran and the West, a confrontation that is about to come to a head, once again, in Vienna. For the first time since President Ebrahim Raisi took office this summer, Iranian negotiators plan to meet with their European, Chinese and Russian counterparts at the end of the month to discuss the future of the 2015 nuclear agreement that sharply limited Iran’s activities.

American officials have warned their Israeli counterparts that the repeated attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities may be tactically satisfying, but they are ultimately counterproductive, according to several officials familiar with the behind-the-scenes discussions. Israeli officials have said they have no intention of letting up, waving away warnings that they may only be encouraging a sped-up rebuilding of the program — one of many areas in which the United States and Israel disagree on the benefits of using diplomacy rather than force.

At the Vienna meeting, American officials will be in the city but not inside the room — because Iran will not meet with them after President Donald J. Trump pulled out of the accord more than three years ago, leaving the deal in tatters. While five months ago those officials seemed optimistic that the 2015 deal was about to be restored, with the text largely agreed upon, they return to Vienna far more pessimistic than when they last left it, in mid-June. Today that text looks dead, and President Biden’s vision of re-entering the agreement in his first year, then building something “longer and stronger,” appears all but gone.

It is a sign of the changed mood that Ali Bagheri Kani, Iran’s newly appointed chief nuclear negotiator, does not refer to the upcoming talks as nuclear negotiations at all. Mr. Bagheri Kani, a deputy foreign minister, said in Paris last week that “we have no such thing as nuclear negotiations.” Instead, he refers to them as “negotiations to remove unlawful and inhuman sanctions.” Iran says it will insist on the lifting of both nuclear and non-nuclear sanctions, and that it needs a guarantee that no future president could unilaterally abandon the agreement, as Mr. Trump did. Biden administration officials say the president would never make such a commitment.

Iran, as always, denies that it has any intention of ever building a nuclear weapon. But the more likely scenario is that it wants a “threshold capability” — one that would leave it able to produce a weapon in weeks or months, if it felt the need.

Publicly, the United States is hinting that if Iran stonewalls in Vienna, it may have to consider new sanctions.

Robert Malley, the State Department’s Iran envoy, said recently that while “it is in Iran’s hands to choose” which path to take, the United States and other allies need to be prepared for whichever choice Tehran makes.

He noted that Mr. Biden and Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken “have both said if diplomacy fails, we have other tools — and we will use other tools to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon.”

But inside the White House, there has been a scramble in recent days to explore whether some kind of interim deal might be possible to freeze Iran’s production of more enriched uranium and its conversion of that fuel to metallic form — a necessary step in fabricating a warhead. In return, the United States might ease a limited number of sanctions. That would not solve the problem. But it might buy time for negotiations, while holding off Israeli threats to bomb Iranian facilities.

Buying time, perhaps lots of it, may prove essential. Many of Mr. Biden’s advisers are doubtful that introducing new sanctions on Iran’s leadership, its military or its oil trade — atop the 1,500 Mr. Trump imposed — would be any more successful than past efforts to pressure Iran to change course.

And more aggressive steps that were successful years ago may not yield the kind of results they have in mind. Inside the National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command, there is consensus that it is much harder now to pull off the kind of cyberattack that the United States and Israel conducted more than a decade ago, when a secret operation, code-named “Olympic Games,” crippled centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear enrichment site for more than a year.

Current and former American and Israeli officials note that the Iranians have since improved their defenses and built their own cyberforces, which the administration warned last week were increasingly active inside the United States.

The Iranians have also continued to bar inspectors from key sites, despite a series of agreements with Rafael M. Grossi, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations’ watchdog, to preserve data from the agency’s sensors at key locations. The inspectors’ cameras and sensors that were destroyed in the plant explosion in late spring have not been replaced.

“From my perspective, what counts is the inspections that you have in place,” Mr. Grossi said in a recent interview in Washington, where he spent a week talking with American officials and warning them that his agency was slowly “going blind” in Iran. He is scheduled to arrive in Tehran on Monday, in a last-ditch effort to revive monitoring and inspections before the agency’s board of governors meets this week.

The inspection gap is particularly worrisome because the Iranians are declaring that they have now produced roughly 55 pounds of uranium enriched to 60 percent purity. That purity is below the 90 percent normally used to produce a weapon, but not by much. It is a level “that only countries making bombs have,” Mr. Grossi said. “That doesn’t mean that Iran is doing that. But it means that it is very high.”

And while Iranian officials have given many explanations for why they are taking the step — for example, to fuel naval nuclear reactors, which Iran does not possess — the real reason seems to be to build pressure.

This month, the spokesman for Iran’s atomic energy agency, Behrouz Kamalvandi, noted with pride that only countries with nuclear weapons have shown that they can enrich uranium to this level. (He is wrong: Several non-nuclear states have done so.)

“In this organization now, if we have the will, we can do anything,” he said.

Before Mr. Trump decided to scrap the deal, Iran had adhered to the limits of the 2015 agreement — which by most estimates kept it about a year from “breakout,” the point where it has enough material for a bomb. While estimates vary, that buffer is now down to somewhere between three weeks and a few months, which would change the geopolitical calculation throughout the Middle East.

When Mr. Biden took office, several of his top aides had high hopes that the original deal — parts of which they had negotiated — could be revived. At that time, the Iranians who had agreed to the accord were still in place: Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, and his foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, remained in office, even if their power was greatly diminished.

But the administration spent two months determining how to approach a negotiation, and European officials complain that, in retrospect, that lost time proved damaging.

It was only at the end of March that the two sides agreed to return to the table; the Vienna talks began in early April.

By June, an agreement “was largely complete,” one senior administration official said. Then it became clear that Iran was stalling until its presidential elections, which brought in Mr. Raisi, a hard-line former head of the judiciary.

Initially, American officials hoped Mr. Raisi would just take the agreement that had been negotiated, make minor alterations and celebrate a lifting of most Western sanctions. Anything that went wrong, they calculated, the new president could blame on the former president and foreign minister.

But that proved a miscalculation. In late September, the country’s new foreign minister, Hossain Amirabdollahian, told The New York Times that he had no interest in conducting the kind of detailed negotiation that his predecessor had worked on for years.

The spokesman for Iran’s foreign ministry, Saeed Khatibzadeh, said at a recent news conference that Iran had three conditions for Washington to return to the deal: It must admit to wrongdoing in pulling out of the deal, it must lift all sanctions at once, and it must offer a guarantee that no other administration will exit the deal as Trump did.

“It is absolutely impossible for Iran to give the level of concession to the U.S. that Rouhani’s government gave,” said Gheis Ghoreishi, a foreign policy adviser close to Iran’s government. “We are not going to give all our cards and then wait around to see if the U.S. or E.U. are going to be committed to the deal or not; this is no way going to happen.”

While European officials say they do not want to consider a “Plan B” if a standoff develops, a variety of such plans — ranging from economic isolation to sabotage — have been the regular subject of meetings at the White House, the Pentagon and the State Department. Asked about the Plan B discussions at a news conference more than two weeks ago, Mr. Biden paused a moment, then said, “I’m not going to comment on Iran now.”

But the Israelis are commenting. This month Israel’s army chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi, said the Israeli military was “speeding up the operational plans and readiness for dealing with Iran and the nuclear military threat.” It was a reference to the fact that the new prime minister, Naftali Bennett, has authorized more funding for planning and practicing attacks. Israeli officials insist they have developed a bunker-busting capability that obviates the need for the kind of help they sought from the Bush administration 13 years ago. Whether that is true or a bluff remains unclear.

At some point, Biden administration officials say they may be forced to declare that Iran’s nuclear program is simply too advanced for anyone to safely return to the 2015 agreement. “This is not a chronological clock; it’s a technological clock,” Mr. Malley said in a briefing last month. “At some point,” he added, the agreement “will have been so eroded because Iran will have made advances that cannot be reversed.”

He added: “You can’t revive a dead corpse.”

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...