A new analysis by Farah Pandith, who is a Senior Fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, explains why children become extremists and how to solve this problem.

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, thousands of young Muslims have embraced extremist ideology, providing terrorist groups with a steady stream of recruits. Puzzling on its face, this phenomenon actually reflects a curious disparity between the attention extremists pay to youth online and that paid by governments. Most governments have done little – despite the rhetoric – to fight extremist ideology online and protect youth. Extremists, meanwhile, have aggressively recruited kids and adolescents online. How can this be? Do extremists love kids more than we do?

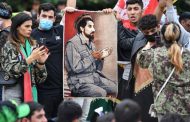

Certainly, extremists depend on young people for their very existence. Indeed, young people – both boys and girls – represent a huge opportunity for these organizations. By 2050, Muslims will number nearly 2.76 billion worldwide, with Islam becoming the world’s largest religion by 2070. With such a large pool of potential recruits, extremists can sustain themselves by snaring just a small percentage of Muslim youth. And that’s exactly what they’re trying to do. Groups like ISIS, al Qaeda, and Boko Haram are investing heavily in grooming the next generation, posting videos of children dressed as suicide bombers or carrying out barbaric acts of violence. A steady stream of online propaganda entices youth by pulling at their emotions. Extremists also use this propaganda to signal to the outside world their intention to play the “long game” and cultivate future generations.

The Crisis of Identity and Sheikh Google

In cultivating youth, extremists have exploited a powerful crisis of identity among Muslim kids the world over. Contrary to popular belief, kids don’t fall prey to extremism because they’re poor and uneducated, although socioeconomic factors do play a role. They fall prey because they are uncertain about who they are, in a way peculiar to our modern times.

Since 9/11, the steady avalanche of “us versus them” messages appearing on and offline has unsettled Muslim youth, sparking a conversation about Muslim identity and its relationship to modernity. As I saw while working with Muslim youth in nearly 100 countries, including many Muslim-majority countries, members of the Millennial and Gen Z generations feel troubled about their identities in a way their parents and grandparents didn’t. Younger Muslims pose questions like: what does it mean to be modern and Muslim? What is a real Muslim? What are the rules? Am I following them?

When struggling with these questions, youth today don’t turn to parents, teachers, and other local authority figures. They go online, consulting what I call Sheikh Google. In an ideal world, the internet would provide youth with positive-minded answers that conform to basic notions of human decency and that accelerate learning about the diversity of belief within Islam. Some answers like that have appeared online, but from the first months after 9/11, a flood of less positive answers have, too. And not merely on Google, but across the internet, a vast space beyond parents’ control.

Unlike governments, which have tried to influence youth by promoting rational arguments such as “we are not at war with Islam” or “Islam does not promote violence,” al Qaeda understood early on that they could use “us versus them” narratives to “solve” the identity crisis for youth and attract them to their cause. They set about delivering youth-friendly messages, ideas, images, and cultural content on platforms that they knew youth frequented. In this way, they built sympathy at the local level while creating virtual “homes” in which kids could seek comfort.

Later, as ISIS, Al Shabaab, Boko Haram, and other terrorist groups formed or expanded, they enhanced these efforts by developing peer-to-peer persuasion, using platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, You Tube, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Kik. For years now, youth have gone online to encounter reassuring answers about belonging, identity, and purpose from a digital army of extremists who are focused specifically on them, and who surround them with messages 24/7.

The so-called underwear bomber, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, was the son of a wealthy Nigerian banker and a student at a London university. Eager for like-minded peers, he went online to ask Sheikh Google questions about being a Muslim. What was good and what was bad to do? How could he navigate the complex waters of daily life? He received ready-made answers in chatrooms and via Anwar Awlawki’s sermons. These answers left him feeling empowered about who he was and what he believed – and eager to partake in violence.

This same process of conversion remains firmly in place today, targeting new groups of youth who might be even more vulnerable than Abdulmutallab was. Take, for instance, the children displaced by conflict in Syria. For thousands of young residents of refugee camps, the identity crisis has been intensified by the emotional and physical trauma of living in a war zone. The extremists understand their plight and have intensified their recruiting in these camps. This is to say nothing of youth who, having fought for ISIS in Iraq and Syria, have returned home. What emotional impact has the war had on them? How dedicated might they still be to extremist ideology? As they form families, how will they shape the views of their children? Without a response from governments, we could be looking at whole new generations of committed extremists.

Protecting our Global Youth

Governments haven’t been entirely inactive in fighting extremist ideology. Some have experimented with unconventional methods to steer kids away from unhealthy ideas. Regardless of the region, we know that in order to protect youth, we must aim messages at them from local influencers—fellow youth. Further, we must deploy those messages consistently over time and at scale, so that it surrounds kids 24/7.

Each neighborhood and each community is different, but with the magic of data-analytics, we have the ability to ensure that local youth are getting the content we want them to get. Unfortunately, local influencers (NGOs and communities-at-large) have lacked the financial resources to disseminate counter-content online at scale. Plugging this gap forms the centerpiece of a winning strategy against extremist recruiting.

Working primarily at the local levels, but coordinating our efforts nationally and internationally, we must create new, comprehensive, online youth protection systems. These systems must draw on a wealth of resources and areas of expertise, including neuroscientific insights about the child-adolescent brain. They should include international networks of online resources for parents, teachers and youth, global partnerships with hospitals and research centers, programs offering one-to-one dialogue with former extremists, and much more.

The solutions exist. The challenge is to mobilize them. Every nation on earth must invest in a strategy that can outpace and out-scale the terrorist recruiters. Every nation must prove in action as well as speech that it loves its kids more than the extremists do.

admin in: How the Muslim Brotherhood betrayed Saudi Arabia?

Great article with insight ...

https://www.viagrapascherfr.com/achat-sildenafil-pfizer-tarif/ in: Cross-region cooperation between anti-terrorism agencies needed

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found ...